Elizabeth Englander

The Elizabethan Lumber Room

17 January–7 March 2026

Opening: Friday 16 January, 6–8 pm

“I borrow not of the ancients, nor read the bookes of men, but the booke of my selfe, and confesse that every man is not onely himselfe; there have beene many Diogenes, and as many Tymons, though but few of that name: men are lived over againe…”

—Sir Thomas Browne, Religio Medici, 1642

“To study the buddha way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things.”

—Dōgen, Genjōkōan, 1233

In her 1925 essay The Elizabethan Lumber Room, Virginia Woolf compares the mind of English polymath Sir Thomas Browne to “a chamber stuffed from floor to ceiling with ivory, old iron, broken pots, urns, unicorns’ horns, and magic glasses full of emerald lights and blue mystery.” The inherited junk room is posited as a metaphor for the psychic residue of empire: the plundered world, interiorized and reorganized as subjectivity. This image is repeated, with greater violence, in the opening of Orlando (1928) when Woolf introduces her hero slicing at an ancestral trophy: a “Moor’s head” that hangs in his attic.

For this exhibition, I organized my own lumber room within several Globe-Wernicke barrister’s bookcases similar to one that had belonged to my grandfather, which I inherited from my mother. Invented in the 1890s and popularized in the early twentieth century, these glass-fronted, modular compartments were designed with expansion and portability in mind, for use primarily in domestic, legal, and administrative contexts. The company’s advertising slogan,“always complete but never finished,” conveys the advantage of their “elastic” system, which anticipates a future piled with ever more books: accumulating literature and legal precedent along with the intellectual acquisitions of imperial progress.

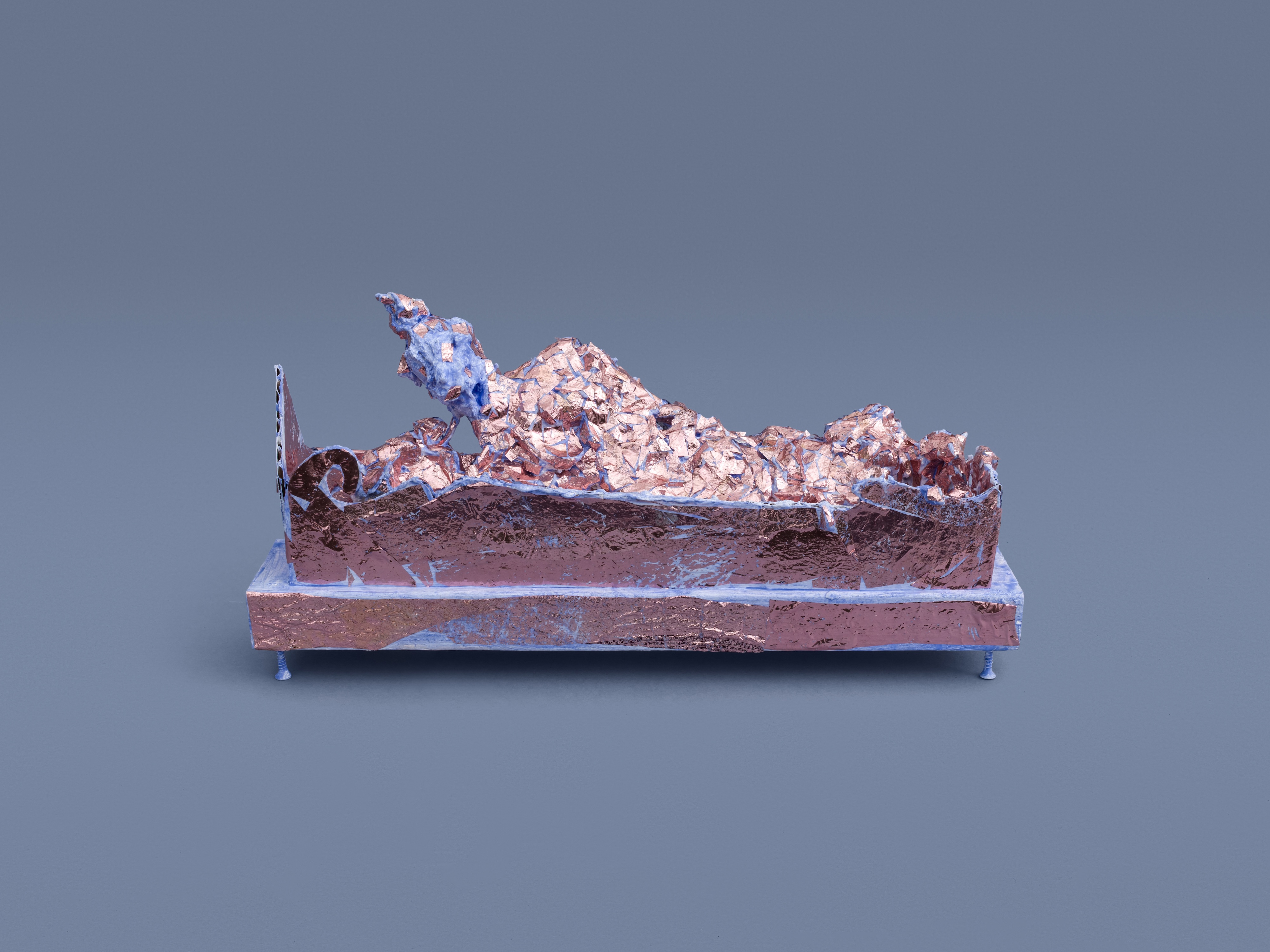

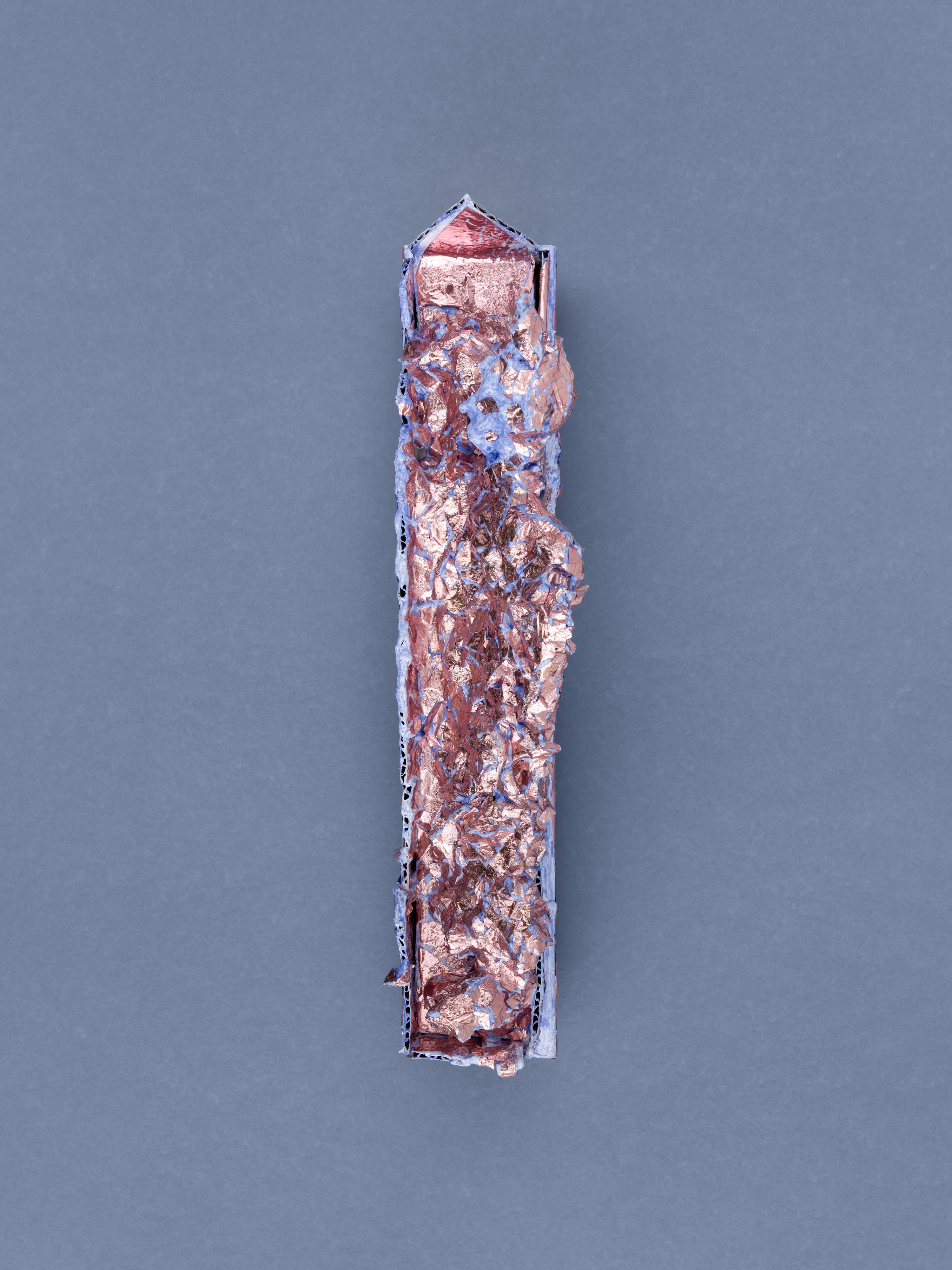

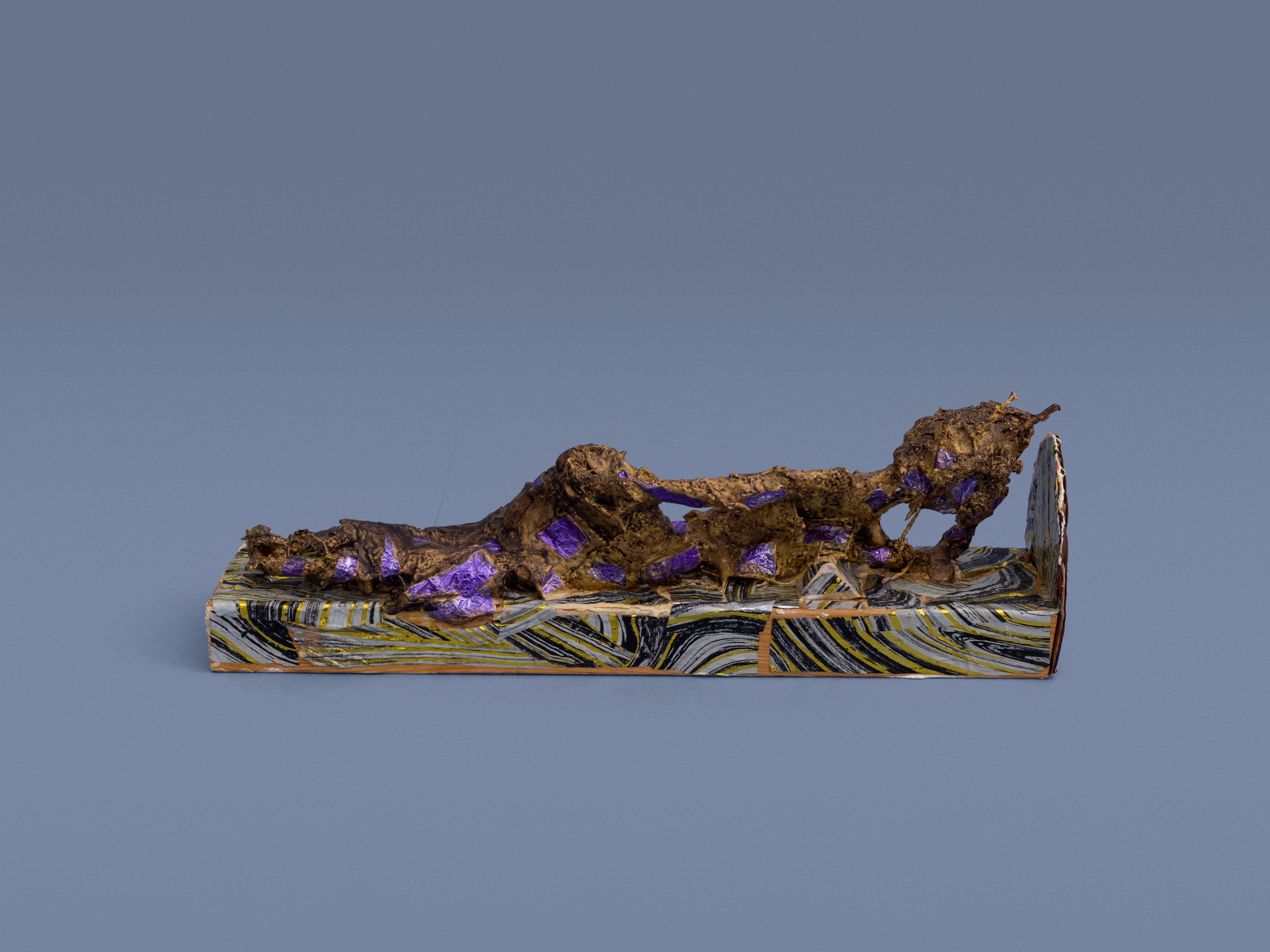

The bookshelves in the gallery are filled with small sculptures of reclining figures. Initially conceived as parinirvanas, or depictions of the death of the Buddha, these works vary in material and (re)pose, hewing to and straying from the traditional iconography.

The earliest representations of the parinirvana are found in Gandharan Buddhist art of the second and third centuries, in which the figure is defined by classically draped robes. To evoke these Buddhas, I folded cloth and dipped it in plaster, or stitched the folds together.

The second typology is the reclining teaching buddha popular in Southeast Asia. Relaxed and approachable, their heads propped on one hand, these figures reminded me of reclining nudes in the European modernist tradition, including those of Henri Matisse and Henry Moore—a third typology, in turn, with which I also worked for this show. To make these pieces, I wrapped plaster-soaked jute around wire armatures, drawing on Moore’s plaster techniques. I then painted and decoupaged them with fragments of found mylar balloons in imitation of the gold leaf often applied to Buddhist icons.

Topping two of the bookcases are Henry Moore studies made from textiles stretched over wire. For these and the other stitched works, I drew from my personal wardrobe. The skin of Parinirvana (UNESCO Betty) is pieced together from a t-shirt I’ve had since college, which features Betty Boop in an American flag dress against a Union Jack background. The sculpture takes the form of Moore’s 1957–58 reclining figure for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. Mapping Betty’s body onto Moore’s biomorph reveals the extent of the distortions in each, while scrambling the British flag into a patchwork that recalls the dazzle camouflage of the First World War.

In the 2010 photograph that serves as the exhibition invitation, I recline on my college bed wearing the same t-shirt along with the worn-off face paint of a faded domino mask, a key signifier in my work at the time, which centred on a persona-based project about a feminist terrorist named Betty who quickly sold out and was gradually subsumed by her namesake avatar, Miss Boop. Elizabeth is a popular name, especially in Anglophone cultures; this popularity has spawned nicknames such as Betty. I came to see Elizabeth, like the image of Boop, as a slippery, universalizing signifier for a female person. In her sellout phase, my Betty made clothing—very poorly—and when I wore those flimsy garments, I recall registering, with great unease, the contingency of my sense of self: in Buddhist terms, its conditional and ultimately empty nature.

In her essay, Woolf suggests that imperialism may have given rise to modern subjectivity (and by extension, individualism) through violent encounters with the other, mediated by material and epistemological appropriation. As empires consolidated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the identities of the colonizers seem to have hardened, especially along racial lines, perhaps driven by fear of difference and the psychological need to dehumanize those they were oppressing. Browne, writing in an earlier phase of this process, seems in contrast to have been comfortable with the Buddhist principle of no-self, whereby “every man is not onely himselfe.” Buddhism offers the possibility of facing this reality with openness, in a posture of wondering surrender—and of observing, with appreciation, the many beings past, present and future with whom the self arises; what Thích Nhất Hanh refers to as “interbeing.”

Alternately (and ambiguously) dead, asleep, teaching, or eroticized, my figures melt into formlessness or find embodiment in scraps of pleated cloth. To me, the folds (and in some works, ruffles) evoke labial or vaginal forms overtaking a toppled phallic structure. In the painted and collaged pieces, the cheap opulence of celebratory mylar animates the half-distinct shapes of teachers, dreamers, corpses, and odalisques. In the textile works, garments with personal significance—a childhood ballet costume, my mother’s kilt—have been sacrificed and retired in novel configurations suggestive of the buddha nature that was always present in them.

Aby Warburg’s concept of Nachleben, or the afterlife of forms, points to the persistence of images across time and cultural transformation. Warburg’s obsessive work on the Mnemosyne Atlas, an attempt to map the art history of certain recurring, emotive gestures—what he referred to as pathosformeln—is thought to have contributed to his mental collapse. While similar inquiry into personal and collective karma is central to Buddhist practice, the Buddha cautioned that speculation about the precise workings of the law of causality “would bring madness and vexation to anyone who conjectured about it.” In tracing my own causes and conditions through this work, therefore, the challenge has been to sit with the vertigo of infinite regress, to remain curious without trying to grasp everything, let alone reconcile it.

There is a famous Zen story about an old man who stumbles and falls while carrying bamboo baskets. His daughter, seeing him fall, rushes to his side and throws herself down beside him. “What are you doing?” he asks. “I saw you fall to the ground, so I’m helping,” she replies. Her gestural mimicry is a form of empathetic, embodied inquiry. In reproducing the creative gesture of the reclining pathosformeln, I have likewise tried to meet some of the myriad things which actualize my selfe and our world.

Elizabeth Englander (b. 1988, Boston, MA, USA) lives and works in New York. She received her MFA from Hunter College in 2019, and her BFA in Painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 2011. Recent solo exhibitions include Mister Poganynibbana, Theta & From the Desk of Lucy Bull, New York (2025); Eminem Buddhism, Volume 3, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT (2024); Eminem Buddhism Vol 2, House of Gaga, Guadalajara (2023); and Eminem Buddhism, Theta, New York (2022). Englander has participated in group exhibitions at By Art Matters, Hangzhou (2024); Company Gallery, New York (2024); Bel Ami, Los Angeles (2024); White Columns, New York (2023); Lomex, New York (2022); What Pipeline, Detroit (2022); Night Gallery, Los Angeles (2021); and Muzeum Ikon, Warsaw (2018). An essay on her relationship to Buddhist sculpture, Wisdom Kings, was published in 2023 by Theta.

Press

Wood, wire, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

15.2 x 44.6 x 8.6 cm

6 x 17 1/2 x 3 3/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0001

Wood, wire, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

15.2 x 44.6 x 8.6 cm

6 x 17 1/2 x 3 3/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0001

Wood, wire, cardboard, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

22.1 x 45.7 x 8.6 cm

8 3/4 x 18 x 3 3/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0002

Wood, wire, cardboard, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

22.1 x 45.7 x 8.6 cm

8 3/4 x 18 x 3 3/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0002

T-shirt, wire, stuffing, thread

39.5 x 54 x 28.5 cm

15 1/2 x 21 1/4 x 11 1/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0003

T-shirt, wire, stuffing, thread

39.5 x 54 x 28.5 cm

15 1/2 x 21 1/4 x 11 1/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0003

Flag, thread

5 x 55.7 x 15 cm

2 x 21 7/8 x 5 7/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0004

Sweater, wire, stuffing, thread

42 x 56 x 24.5 cm

16 1/2 x 22 x 9 5/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0005

Sweater, wire, stuffing, thread

42 x 56 x 24.5 cm

16 1/2 x 22 x 9 5/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0005

Kilt, thread

8.5 x 68.6 x 10.2 cm

3 3/8 x 27 x 4 in

AS-ENGLE-0006

Kilt, thread

8.5 x 68.6 x 10.2 cm

3 3/8 x 27 x 4 in

AS-ENGLE-0006

Wood, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

14.5 x 36 x 12.5 cm

5 3/4 x 14 1/8 x 4 7/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0007

Wood, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

14.5 x 36 x 12.5 cm

5 3/4 x 14 1/8 x 4 7/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0007

Wood, wire, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar, glitter

20.8 x 44.7 x 16.5 cm

8 1/4 x 17 5/8 x 6 1/2 in

AS-ENGLE-0008

Wood, wire, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

26 x 35.7 x 18.6 cm

10 1/4 x 14 x 7 3/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0009

Wood, wire, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

26 x 35.7 x 18.6 cm

10 1/4 x 14 x 7 3/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0009

Wood, cork, hydrocal, cheesecloth, paint, mylar

15 x 45.8 x 19 cm

5 7/8 x 18 x 7 1/2 in

AS-ENGLE-0010

Wood, cork, hydrocal, cheesecloth, paint, mylar

15 x 45.8 x 19 cm

5 7/8 x 18 x 7 1/2 in

AS-ENGLE-0010

Dance costume, stuffing, thread

14.5 x 61 x 23 cm

5 3/4 x 24 x 9 in

AS-ENGLE-0011

Wood, wire, cardboard, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

14.2 x 43.5 x 9.5 cm

5 5/8 x 17 1/8 x 3 3/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0012

Wood, wire, cardboard, hydrocal, jute, paint, mylar

14.2 x 43.5 x 9.5 cm

5 5/8 x 17 1/8 x 3 3/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0012

Dress, thread

7.5 x 66 x 17 cm

3 x 26 x 6 3/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0013

Dress, thread

7.5 x 66 x 17 cm

3 x 26 x 6 3/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0013

Old sock, thread, wire

Laid flat: 13 x 18 cm

5 1/8 x 7 1/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0014

Old sock, thread, wire

Laid flat: 12.2 x 17 cm

4 3/4 x 6 3/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0015

Old sock, thread, wire

Laid flat: 18 x 16.5 cm

7 1/8 x 6 1/2 in

AS-ENGLE-0016

Old sock, thread, wire

Laid flat: 12 x 19.3 cm

4 3/4 x 7 5/8 in

AS-ENGLE-0017

Old sock, thread, wire

Laid flat: 17 x 17 cm

6 3/4 x 6 3/4 in

AS-ENGLE-0018